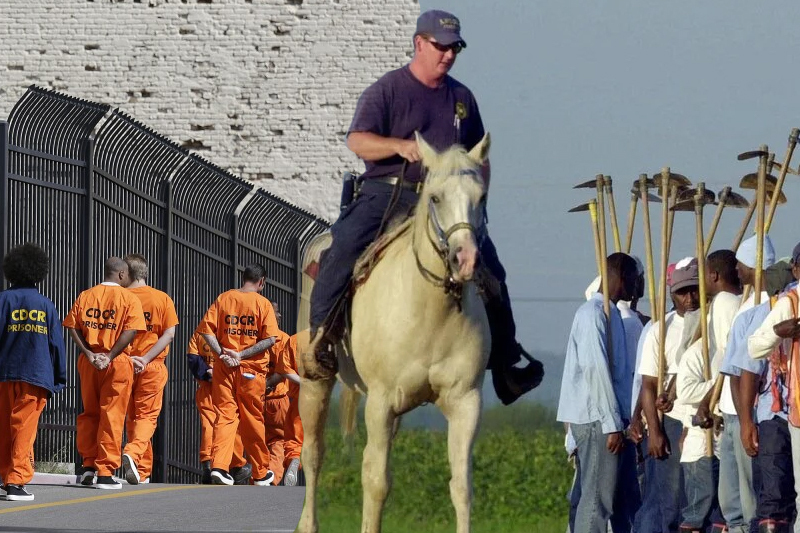

us prison work breaks bodies and minds for pennies

Last updated on September 20th, 2023 at 11:44 am

United States – Susan Dokken, who is enrolled in a halfway house re-entry programme in California, continued to work during her prison sentence despite having a stroke and needing more assistance, which was disregarded.

United States – Susan Dokken, who is enrolled in a halfway house re-entry programme in California, continued to work during her prison sentence despite having a stroke and needing more assistance, which was disregarded.

Dokken, 60, said, “I couldn’t work and wasn’t supposed to, and I couldn’t even talk for a year.”

She was assigned to prepare lunches at a nearby men’s prison during the pandemic even though she didn’t feel secure doing so and had untreated medical conditions like anaemia and the need for dentures she never got.

Two out of every three of the more than 1.2 million Americans who are detained in federal and state prisons are required to work while incarcerated. Prison labour has been compared to modern-day slavery by detractors of the US constitution’s 13th amendment, which outlawed slavery or involuntary servitude but made an exception for inmates.

Dokken’s salary began at 12 cents per hour, and after receiving excellent feedback, inmates were given the option of raising it to 24 cents per hour. However, they are still paid full price when purchasing necessities from the commissary.

Dokken added that inmates who refused to labour would have their privileges taken away and could receive a written warning, which would be recorded on their record and affect their eligibility for parole and probation.

Prior to working in the men’s jail, Dokken made clothes for the US military. Her compensation of a few cents an hour would be decreased if she or other prisoners didn’t meet a production goal of 2,500 shorts each day.

The American Civil Liberties Union reported in June 2022 that the annual revenue earned by prison labour is more than $11 billion, with more than $2 billion coming from the manufacture of commodities and more than $9 billion coming from maintenance services. The hourly pay ranges from 13 cents to 52 cents on average, but many convicts receive no pay at all, and those who do receive pay are subject to several deductions.

Over the previous ten years, Sarah Corley has spent time behind bars in both Missouri and Georgia. While in Georgia, she worked unpaid while confined, while in Missouri, her salary ranged from a few cents to a few dollars per day, depending on the job.

Related Posts

Corley, an artist, claimed that when she was detained, the correctional staff regularly commissioned her to create art for their personal use as one of her job assignments, without paying her anything. Today, Corley sells her paintings for a few hundred dollars each.

The staff was receiving my incredibly expensive artwork for free, claimed Corley. “I received images of my completed work as payment. Being that the majority of them are a 16 by 20 foot canvas, there are about 25 pieces total, it was kind of mind-blowing to realize how many pieces I had just created for nothing. These officers recently received them for nothing, but I currently sell them for $400 to $600.”

According to Corley, it’s challenging to work in prison when basic requirements are so expensively priced at the prison commissary and convicts aren’t given enough food or other necessities. She claimed that if you don’t already have money or have someone else deposit money into your account, it is difficult to take care of yourself. In jail conditions, Corley said, there is no time for rest or recovery from work; instead, you must compete for a shower or wait in line.

While incarcerated, she also worked for the Department of Transportation, maintaining lawns, collecting trash and roadside dead animals, and applying pesticides without any on-the-job training or any safety precautions.

Those are labor-intensive tasks, particularly for women, and even if you were paid for them, your body would suffer. You’re doing things that you wouldn’t choose to do, like chopping down trees while toting incredibly large backpacks filled with poisons. It takes a lot of labour for nothing, she complained.

According to the ACLU report, 76% of the workers polled said they were forced to work or faced additional punishment; 70% said they could not afford basic necessities on the wages they received for their prison labour; 70% said they did not receive any formal job training; and 64% expressed concerns for their safety at work.

Prison employees are also exempt from the fundamental labour protections provided by federal and state laws, as well as from the rights of workers to basic wage laws, union rights, and safety regulations.

The work can range from janitorial, food preparation, maintenance and repair, or other essential services to public works projects like construction, prison industries that supply goods and services to other government agencies through state-owned corporations, or producing goods and services for a private corporation.

James Finch claimed he was ordered back to work after visiting the hospital for heat exhaustion when he initially worked outside doing landscaping labour while incarcerated in Florida roughly ten years ago.

Without supervision or training, he later worked at a recycling facility while incarcerated. While there, he began to experience the symptoms of Bell’s Palsy, which causes partial facial paralysis, but he chose not to seek proper treatment because doing so would have required him to travel several times a week in a prison van to the hospital while shackled.

Finch claimed, “I never was paid a dime for any of the work I had done. Although it usually does, “I hoped my face would return to normal.”

Aisha Northington, a Georgia inmate who was released from prison in 2011, completed all of her sentence’s required duties without receiving any payment.

According to Northington, “I’ve even seen some folks who refused and were put in solitary confinement.” It is quite discouraging. It has to end. That is inhumane.